Zitkála-Šá: Episode transcript

Get the full story...

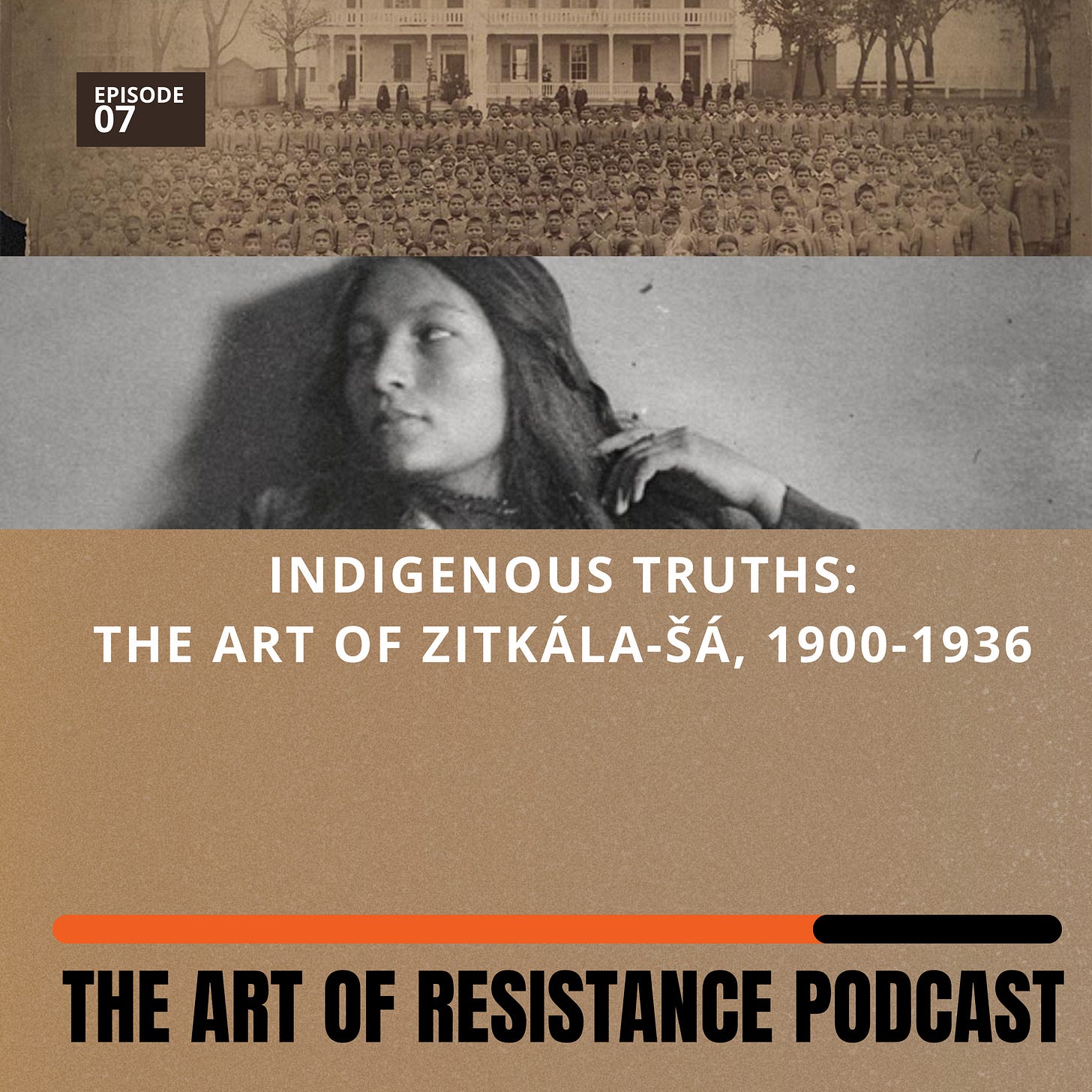

Indigenous truths: The art of Zitkála-Šá, 1900-1936

This episode is presented by The Indigenous Art Alliance, a non-profit organization promoting and empowering Indigenous artists through Contemporary Arts. The Indigenous Peoples Art Gallery and Cafe in Iowa City, Iowa, is a space for Indigenous Arts events. Our vision is to be a unique space for the Midwest region providing a place to learn about history of Indigenous people with an emphasis on Iowa’s historical tribal nations. Learn more at indigenousartalliance.org.

Clip: P. Jane Hefen on her voice, and political role

Music: The Shannon Quartet - Let Me Call You Sweetheart @Pax41

Narration:

She may have been the first. The first Indigenous American to speak in her own voice, instead of white Americans speaking for her. The first to use essays, and oral tradition stories, and official reports, and even operas, to talk about the realities of Native American life and demand change.

And in the process, she pushed against the supposedly immovable force of the Bureau of Indian Affairs and the national government. Earning enemies and punishment along the way.

While many may know of the American Indian Movement in the 1960s and 70s, which occupied government buildings, Wounded Knee, and Alcatraz, lesser known is the creative work and life of the indigenous woman in the early 1900s who paved the way.

Music: Song No. 3 • Catalog No. 648 Densmore recording sung by Matȟó Itȟúŋkasaŋ (Weasel Bear)

How did writing empower a community? How did truth-telling defy the powers that be, and embolden generations to come? And what can we learn from Zitkála-Šá about how to make art as resistance today and tomorrow?

From Rebel Yell Creative, this is The Art of Resistance, a podcast about channeling our rage into creation, and using writing, music, and all kinds of art to resist the status quo.

I’m your host and producer Amy Lee Lillard, and I’m an author, podcaster, and autistic person who’s been obsessing over artists who resisted since I was a kid. And today, I’m looking to make all the weird art, and help others do the same.

PART 1: THE LAND OF APPLES

That song comes from the Densmore recordings, a collection of live music by Sioux tribal members in the early 1900s.

She was born as Gertrude on the Yankton Dakota Sioux Reservation in South Dakota in 1876. In essays that she wrote later, she described a quiet yet vibrant childhood, surrounded by mother, aunts, and her people.

But at the same time, she felt her mother’s deep sadness.

Reaches for the Wind was of the first Native American generation forced to adapt to reservation life. She would talk of the past, the before. They were happy, she said, but the paleface stole their lands and drove us here.

When Gertrude was 8 years old, missionaries arrived in the reservation. They talked to the children, spinning tales of riding on an iron horse to a land full of apples. They asked the kids to join them.

She was thrilled by the stories, and begged her mother to let her go.

Immediately, she realized her mistake.

PART 2: ERASED

She rode the train to Wabash, Indiana, to the Quaker-run boarding school. There her long hair, tied to her home, to her culture, was quickly chopped off. She found the apple orchard, but the apples were dying off. The school was cold, and hard, and the nights were filled with crying.

The Wabash school was just one of a system of schools designed to forcibly assimilate indigenous people. And by assimilate, the federal government meant erase. The schools outlawed the children’s tribal languages. They banned cultural practices and religious traditions. The kids were beaten and punished when they broke these rules.

Clip: Kill the Indian but save the man - Virgil Taken Alive, Board Member, Standing Rock Elders Preservation Council

The schools acted as part of the broader Bureau of Indian Affairs philosophy and methods. Starting in 1883, the Indian Offenses Act outlawed traditional native practices and religious observances, like the Sioux Sun Dance.

A few years into school, Gertrude returned to her mother on the reservation. But like immigrant kids, or minority kids in majority culture, she found she’d been irrevocably changed. She didn’t fit like she used to. There was a wedge between her and her mother, and the broader community. She’d been devastated at school, and homesick, but now that she was home, she was devastated again.

In later essays, she wrote: “My mother had never gone inside of a schoolhouse, and so she was not capable of comforting her daughter who could read and write. Even nature seemed to have no place for me. I was neither a wee girl nor a tall one; neither a wild Indian nor a tame one.”

So she went back to school. She played the game. She graduated, and went to college, and studied violin, and eventually became a teacher at another boarding school, run by a military officer Pratt.

“Often I wept in secret, wishing I had gone West to be nourished by my mother’s love instead of remaining among a cold race whose hearts were frozen hard by prejudice.”

PART 3: RED BIRD

In 1900, the school sent her back to her reservation to recruit more students. She was shocked at what she found.

The family home was falling apart. The people on the rez lived in deep poverty. And worst of all, white settlers were occupying their land.

She went back to school with critical eyes, and saw again the torment she experienced as a child. She saw how the school deeply restricted what the kids learned. She saw how they were set up to live like the folks back home.

And she started to write.

Music: Clear the Way (Song 136)

Under her new name of Zitkála-Šá, which meant Red Bird in Sioux, she wrote personal essays describing her idyllic childhood, and then her traumatic schooling. She talked about the deep pain she felt, and the inherent cruelty of schools stealing children and erasing their culture.

When the essays appeared in Atlantic and Harper’s in early 1900, she was fired from the school.

She went back to the reservation, and worked as a clerk for the tribal offices. She also collected oral stories told in Sioux from elders down the line. The stories became a book, Old Indian Legends, the first to translate the stories and preserve them for future generations.

She also wrote an article in The Atlantic called “Why I am a Pagan.”

[Reading from the book]

During this time she married, and together they moved to the Ute reservation in Utah to work for the reservation there.

In 1910, she met a white professor at BYU who was interested in the tribal practice of the Sun Dance. It was a sacred Sioux ritual that had been banned by the government, just like so many rituals and religious practices across tribes. Together, they created the Sun Dance opera, a unique piece of art bridging two cultures.

P. Jane Hefen, the editor of a 2001 book that brought together the Sun Dance Opera and additional writings, spoke about this in the Unsung History podcast.

Clip on Sun Dance

This is the opening song of the Sun Dance.

Song No. 19 • Catalog No. 479 Densmore recording sung by Išnála Wičhá (Lone Man)

In 1921, she brought together many of her essays, along with additional stories, into another book, American Indian Stories.

Later, Zitkála-Šá also published a report entitled "Oklahoma’s Poor Rich Indians." This article was instrumental in getting the government to investigate the exploitation and defrauding of Native Americans by outsiders for access to oil-rich lands.

PART 4: CITIZENSHIP

While Zitkála-Šá and her husband lived in Utah, they saw the deeply racist treatment of the federal officials against the Uintah and Ouray peoples. Witnessing this, and remembering her own experiences in Sioux land, she joined the Society of American Indians.

They were founded by and run by Native peoples. They wanted to end the corrupt and violent reservation system keeping the indigenous peoples poor and cut off from culture. But even more than that, they wanted enfranchise native peoples, giving them citizenship and the right to vote.

Zitkala edited the American Indian magazine from the society, and used her voice and her writing to spread the word about this mission. In many instances, her writing previewed would later be known as the Red Power movement in the 70s – abolishing he Bureau of Indian Affairs, allowing all native cultural practices, retention or even reclaiming of lands, and even the tenet that indigenous culture was morally superior to white colure.

By the end of World War I, the citizenship and voting issue gained even more urgency. 25% of the adult male Native population had served in the war, compared to 15% of all other American males. Her position: If the Indian is good enough to fight for America, he is good enough to be considered American, with all the rights and privileges associated.

At the same time, Zitkala was working deep in the suffrage movement. she helped the efforts that led to the Nineteenth Amendment in 1920. She then traveled around the U.S., calling on white women to use their newly won suffrage rights to enfranchise Native peoples. In 1924, in part due to Zitkála-Šá’s advocacy, Congress passed the Indian Citizenship Act that endowed full citizenship rights to all native-born people in the country.

However, this did not guarantee the vote. States retained the authority to decide who could and could not vote. Some states began to adopt strategies similar to Jim Crow laws to disenfranchise Native people.

So Zitkála-Šá and her husband founded the National Council of American Indians in 1926, an organization that went further than others, working explicitly for universal suffrage. F or the rest of her life, she served as president, fundraiser, and speaker.

PART 5: IMPACT

From everything mentioned about Zitkala so far, you’d think she was a slam dunk of a indigenous pioneer and hero.

But in many ways, her legacy has been controversial.

After marriage and a child, Zitkala-Šá did an about-face. After writing about proudly being a pagan, and declaring the Christian-led schools as violent and wrong, she became a Catholic. This, combined with the fact that she worked for the Quaker schools for a time, led some activists and indigenous folks to look at Zitkala-Šá with suspicion.

Also, she became fixated on the use of peyote in indigenous populations. The drug was often used in religious ceremonies, and she watched it grow among the Ute. She claimed that peyote was a deadly danger, and not truly aligned with their culture but spread by outside influence. In her anti-Peyote campaign, she allied with some of the biggest enemies of Native peoples, including leadership of the Bureau of Indian Affairs.

Finally, when Zitkala-Šá created the Sun Dance opera, it was problematic from the start. She was Dakota, which did not use the Sun Dance as much as the Lakota. But she also had the bad fortune to partner with a grifter. When she worked with the white BYU professor to make the Sun Opera in 1913, they adapted the ritual to appeal to native and white audiences. And then in 1938, the professor cut her out, creating new productions without crediting her work and stripping out much of the realism.

Clip: P. Jane Hefen on perception from critics

But the truth is much more complicated.

Zitkala-Šá was writing and speaking in a time where she had to walk a tightrope. The image of Native Americans was so terrible in mainstream society that she had to balance writing the truth with not alienating her audience. She had to play the game of respectability politics that so many groups have to play even now. She had to navigate a government was was brutal and mercenary. And during World War I and after, she had to work around stringent censorship laws.

When Zitkala-Šá converted to Catholicism, it was in a time when the Catholic Church frequently partnered with Native American support organizations and the overall cause. When she came out against peyote, it was at a time when women’s suffrage movements were often deeply tied to anti-alcohol and drug movements. And everyone has bad luck sometimes when it comes to collaborators.

When it comes down to it, Zitkala-Šá was a complicated person, just like everyone. She was built from erased and manufactured culture, torn apart in many ways. She tried to work within systems just as often as she tried to tear them down. She exemplified the paradoxes that a colonized population face.

And she gave a platform to indigenous voices at a time when the only voices were white ones, spreading the lies about degenerate and child-like Native peoples that needed a firm white hand.

Clip – P. Jane Hefen on legacy

CONCLUSION:

What can we learn from Zitkála-Šá? What can we do as creative people in this fucked-up world?

Because we are all creative. We can all finds ways to resist.

Today Zitkala-Šá is increasingly recognized as a huge pioneer in Indigenous rights and representation. And the key tenets of much of her writing and activist work appeared in similar forms in the “20-Point Indian Manifesto” and other demands from the Red Power organizations in the 1970s.

Her story is one of finding her voice, and then giving voice to others like her. And that story isn’t pure, by some accounts. But whose is?

Sticking rigidly to one viewpoint and never changing is not a badge of honor in real life. That’s one thing I think we can take from Zitkala-Sa’s story. We are people who live and change and evolve. And not only that, women face unique pressures on our public viewpoints, as do BIPOC peoples.

Despite all that, Zitkala-Šá did the work. She wrote the things. She told her stories, and those of her family and culture. She pushed as hard as she could against the status quo, and created art to change it.

So here’s what we do from here:

· We tell our stories, in our voice.

· We embrace our cultures, and create work to honor them.

· We create revolutionary art to reach the people who need to see it and hear it.

· And we don’t think of this as short term. Even if we get a new administration down the road, even if we miraculously come out of this terrifying, tyrannical moment, there is so much to fight against and for. This is a long-term commitment to making art for a better world.

OUTRO:

The Art of Resistance is a podcast from Rebel Yell Creative, which is creative consulting, courses and community for good work, good art, and good people. We help community groups, small businesses and creative individuals dedicated to intersectionality and resistance build, create, and resist.

If you’re a creative looking to make art as resistance, subscribe at rebelyellcreative.com.

And if you have a story about making art as resistance that we should feature on the show, one from the past, or one from today, send us a note! Find the link in the show notes.

This is Amy Lee Lillard, and I wrote, narrated, and produced this show. Check the show notes for all sources, and some great additional reading and watching. All transcripts, art, and videos are at theartofresistancepodcast.com.

I’ll see you next time.

SOURCES AND FURTHER READING

“Zitkala-Šá: A Trailblazer for Native American Rights and Cultural Preservation,” Native Hope.

“Zitkala-Ša (Red Bird / Gertrude Simmons Bonnin”, National Park Service.

“Zitkála-Šá ("Red Bird"/Gertrude Simmons Bonnin),” National Women’s History Museum.

“Zitkála-Šá,” Aktá Lakota Museum and Cultural Center.

“Zitkála Šá,” Unsung History Podcast.

“The Sun Dance,” Densmore Repatriation Project.

Red Bird, Red Power: The Life and Legacy of Zitkala-Šá, Tadeusz Lewandowski.

American Indian Stories, Zitkala-Šá.

Old Indian Legends, Zitkala-Šá

Dreams and Thunder: Stories, Poems, and The Sun Dance Opera, Zitkala-Šá.

If you like The Art of Resistance, the best way to show your support is a paid subscription. This is independently produced art, and subscribing helps keep the show going!

Other ways to show your support: Share the show with your friends; order original art and goods; buy a book; and/or join the Rebel Yell Creative community!